Europe Since 1600: A Concise History by Nicole V. Jobin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Europe Since 1600: A Concise History by Nicole V. Jobin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

The creation of this work, Europe Since 1600: A Concise History was supported by Open CU Boulder 2022-2023, a grant funded by the Colorado Department of Higher Education with additional support from the CU Office of the President, CU Office of Academic Affairs, CU Boulder Office of the Provost, and CU Boulder University Libraries.

This book is an adaptation of Western Civilization: A Concise History, volumes 2 and 3, written by Christopher Brooks. The original textbook, unless otherwise noted, was published in three volumes under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA Licence. Published in 2019, with updates in 2020 available on the Open Textbook Library website. The new and revised material in this adaptation is copyrighted 2023 by the adapting author, Nicole V. Jobin, and is released under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 License.

The revisions include the addition of sections in each chapter such as terms for identification, timelines, and questions for discussion. Other specific adaptations are listed at the end of each chapter. In general, typographical errors were corrected and language was occasionally revised to improve clarity. This textbook can be referenced. In Chicago citation style, it should appear as follows: Jobin, Nicole V. Europe Since 1600: A Concise History, Boulder: Pressbooks Buffscreate, 2023. https://pressbooks.buffscreate.net/europesince1600concise/.

Cover Image created by Nicole V. Jobin using Adobe Express. Image: adaptation of 1706 De La Feuille Map of Europe – Geographicus by Daniel de la Feuille, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1706_De_La_Feuille_Map_of_Europe_-_Geographicus_-_Europe-lafeuille-1706.jpg

Nicole V. Jobin is a Teaching Associate Professor (Senior Instructor) and Interim Program Director at CU Boulder’s Stories and Societies Residential Academic program (SRAP), with over 20 years of teaching experience and expertise in undergraduate education. She teaches European history courses for both SRAP and the Department of History and an interdisciplinary course focused on history, economics, globalization, and the environment for SRAP. She is passionate about making the past come alive through access to documents, artifacts, and archives that encourage students to make meaning of the past and their present.

This textbook covers European history since about 1600. Until recently, European history, at least in the form of a typical college survey course, was often styled the history of “Western Civilization.” In putting together the current version of this text, the term “Western Civilization” was taken out of the title, but Christopher Brooks’ original introduction, focusing on the meaning of the term and how it has been studied, is still relevant and has been included below.

Nicole V. Jobin

University of Colorado Boulder

Spring 2023

What is “Western Civilization”? Furthermore, who or what is part of it? Like all ideas, the concept of Western Civilization itself has a history, one that coalesced in college textbooks and curriculums for the first time in the United States in the 1920s. In many ways, the very idea of Western Civilization is a “loaded” one, opposing one form or branch of civilization from others as if they were distinct, even unrelated. Thus, before examining the events of Western Civilization’s history, it is important to unpack the history of the concept itself.

The obvious question is “west of what”? Likewise, where is “the east”? Terms used in present-day geopolitics regularly make reference to an east and west, as in “Far East,” and “Middle East,” as well as in “Western” ideas or attitudes. The obvious answer is that “the West” has something to do with Europe. If the area including Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Israel – Palestine, and Egypt is somewhere called the “Middle” or “Near” East, doesn’t that imply that it is just to the east of something else?

In fact, we get the original term from Greece. Greece is the center-point, east of the Balkan Peninsula was east, west of the Balkans was west, and the Greeks were at the center of their self-understood world. Likewise, the sea that both separated and united the Greeks and their neighbors, including the Egyptians and the Persians, is still called the Mediterranean, which means “sea in the middle of the earth” (albeit in Latin, not Greek – we get the word from a later “Western” civilization, the Romans). The ancient civilizations clustered around the Mediterranean treated it as the center of the world itself, their major trade route to one another and a major source of their food as well.

To the Greeks, there were two kinds of people: Greeks and barbarians (the Greek word is barbaros). Supposedly, the word barbarian came from Greeks mocking the sound of non-Greek languages: “bar-bar-bar-bar.” The Greeks traded with all of their neighbors and knew perfectly well that the Persians and the Egyptians and the Phoenicians, among others, were not their inferiors in learning, art, or political organization, but the fact remains that they were not Greek, either. Thus, one of the core themes of Western Civilization is that right from its inception, of the east being east of Greece and the west being west of Greece, and of the world being divided between Greeks and barbarians, there was an idea of who is central and superior, and who is out on the edges and inferior (or at least not part of the best version of culture).

In a sense, then, the Greeks invented the idea of west and east, but they did not extend the idea to anyone but themselves, certainly including the “barbarians” who inhabited the rest of Europe. In other words, the Greeks did not have a concept of “Western Civilization,” just Greek vs. barbarian. Likewise, the Greeks did not invent “civilization” itself; they inherited things like agriculture and writing from their neighbors. Neither was there ever a united Greek empire: there was a great Greek civilization when Alexander the Great conquered what he thought was most of the world, stretching from Greece itself through Egypt, the Middle East, as far as western India, but it collapsed into feuding kingdoms after he died. Thus, while later cultures came to look to the Greeks as their intellectual and cultural ancestors, the Greeks themselves did not set out to found “Western Civilization” itself.

While many traditional Western Civilization textbooks start with Greece, this one does not. That is because civilization is not Greek in its origins. The most ancient human civilizations arose in the Fertile Crescent, an area stretching from present-day Israel – Palestine through southern Turkey and into Iraq. Closely related, and lying within the Fertile Crescent, is the region of Mesopotamia, which is the area between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in present-day Iraq. In these areas, people invented the most crucial technology necessary for the development of civilization: agriculture. The Mesopotamians also invented other things that are central to civilization, including:

Cities: note that in English, the very word “civilization” is closely related to the word “civic,” meaning “having to do with cities” as in “civic government” or “civic duty.” Cities were essential to sophisticated human groups because they allowed specialization: you could have some people concentrate all of their time and energy on tasks like art, building, religious worship, or warfare, not just on farming.

Bureaucracy: while it seems like a prosaic subject, bureaucracy was and remains the most effective way to organize large groups of people. Civilizations that developed large and efficient bureaucracies grew larger and lasted longer than those that neglected bureaucracy. Bureaucracy is, essentially, the substitution of rules in place of individual human decisions. That process, while often frustrating to individuals caught up in it, does have the effect of creating a more efficient set of processes than can be achieved through arbitrary decision-making. Historically, bureaucracy was one of the most important “technologies” that early civilizations developed.

Large-scale warfare: even before large cities existed, the first towns were built with fortifications to stave off attackers. It is very likely that the first kings were war leaders allied with priests.

Mathematics: without math, there cannot be advanced engineering, and without engineering, there cannot be irrigation, walls, or large buildings. The ancient Mesopotamians were the first people in the world to develop advanced mathematics in large part because they were also the most sophisticated engineers of the ancient world.

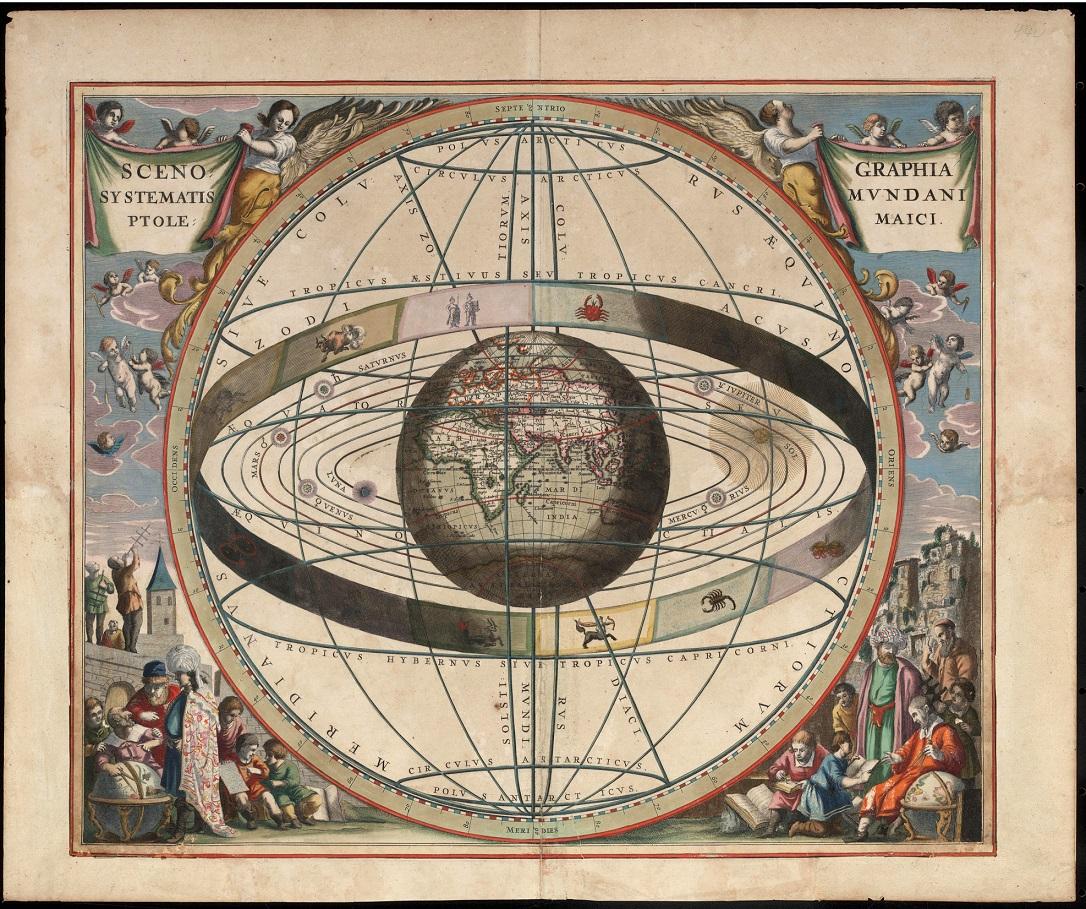

Astronomy: just as math is necessary for engineering, astronomy is necessary for a sophisticated calendar. The ancient Mesopotamians began the process of systematically recording the changing positions of the stars and other heavenly bodies because they needed to be able to track when to plant crops, when to harvest, and when religious rituals had to be carried out. Among other things, the Mesopotamians were the first to discover the 365 (and a quarter) days of the year and set those days into a fixed calendar.

Empires: an empire is a political unit comprising many different “peoples,” whether “people” is defined linguistically, religiously, or ethnically. The Mesopotamians were the first to conquer and rule over many different cities and “peoples” at once.

The Mesopotamians also created systems of writing, of organized religion, and of literature, all of which would go on to have an enormous influence on world history, and in turn, Western Civilization. Thus, in considering Western Civilization, it would be misleading to start with the Greeks and skip places like Mesopotamia, because those areas were the heartland of civilization in the whole western part of Eurasia.

Even if we do not start with the Greeks, we do need to acknowledge their importance. Alexander the Great was one of the most famous and important military leaders in history, a man who started conquering “the world” when he was eighteen years old. When he died his empire fell apart, in part because he did not say which of his generals was to take over after his death. Nevertheless, the empires he left behind were united in important ways, using Greek as one of their languages, employing Greek architecture in their buildings, putting on plays in the Greek style, and of course, trading with one another. This period in history was called the Hellenistic Age. The people who were part of that age were European, Middle Eastern, and North African, people who worshiped both Greeks gods and the gods of their own regions, spoke all kinds of different languages, and lived as part of a hybrid culture. Hellenistic civilization demonstrates the fact that Western Civilization has always been a blend of different peoples, not a single encompassing group or language or religion.

Perhaps the most important empire in the ancient history of Western Civilization was ancient Rome. Over the course of roughly five centuries, the Romans expanded from the city of Rome in the middle of the Italian peninsula to rule an empire that stretched from Britain to Spain and from North Africa to Persia (present-day Iran). Through both incredible engineering, the hard work of Roman citizens and Roman subjects, and the massive use of slave labor, they built remarkable buildings and created infrastructure like roads and aqueducts that survive to the present day.

The Romans are the ones who give us the idea of Western Civilization being something ongoing – something that had started in the past and continued into the future. In the case of the Romans, they (sometimes grudgingly) acknowledged Greece as a cultural model; Roman architecture used Greek shapes and forms, the Roman gods were really just the Greek gods given new names (Zeus became Jupiter, Hades became Pluto, etc.), and educated Romans spoke and read Greek so that they could read the works of the great Greek poets, playwrights, and philosophers. Thus, the Romans deliberately adopted an older set of ideas and considered themselves part of an ongoing civilization that blended Greek and Roman values. Like the Greeks before them, they also divided civilization itself in a stark binary: there was Greco-Roman culture on the one hand and barbarism on the other, although they made a reluctant exception for Persia at times.

The Romans were largely successful at assimilating the people they conquered. They united their provinces with the Latin language, which is the ancestor of all of the major languages spoken in Southern Europe today (French, Italian, Spanish, Romanian, etc.), Roman Law, which is the ancestor of most forms of law still in use today in Europe, and the Roman form of government. Along with those factors, the Romans brought Greek and Roman science, learning, and literature. In many ways, the Romans believed that they were bringing civilization itself everywhere they went, and because they made the connection between Greek civilization and their own, they played a significant role in inventing the idea of Western Civilization as something that was ongoing.

That noted, the Romans did not use the term “Western Civilization” and as their empire expanded, even the connection between Roman identity and Italy itself weakened. During the period that the empire was at its height the bulk of the population and wealth was in the east, concentrated in Egypt, Anatolia (the region corresponding to the present-day nation of Turkey) and the Levant. This shift to the east culminated in the move of the capital of the empire from the city of Rome to the Greek town of Byzantium, renamed Constantinople by the empire who ordered the move: Constantine. Thus, while the Greco-Roman legacy was certainly a major factor in the development of the idea of Western Civilization much later, “Roman” was certainly not the same thing as “western” at the time.

Another factor in the development of the idea of Western Civilization came about after Rome ceased to exist as a united empire, during the era known as the Middle Ages. The Middle Ages were the period between the fall of Rome, which happened around 476 CE, and the Renaissance, which started around 1300 CE. During the Middle Ages, another concept of what lay at the heart of Western Civilization arose, especially among Europeans. It was not just the connection to Roman and Greek accomplishments, but instead, to religion. The Roman Empire had started to become Christian in the early fourth century CE when the emperor Constantine converted to Christianity. Many Europeans in the Middle Ages came to believe that, despite the fact that they spoke different languages and had different rulers, they were united as part of “Christendom”: the kingdom of Christ and of Christians.

Christianity obviously played a hugely important role in the history of Western Civilization. It inspired amazing art and music. It was at the heart of scholarship and learning for centuries. It also justified the aggressive expansion of European kingdoms. Europeans truly believed that members of other religions were infidels (meaning “those who are unfaithful,” those who worshipped the correct God, but in the wrong way, including Jews and Muslims, but also Christians who deviated from official orthodoxy) or pagans (those who worshipped false gods) who should either convert or be exterminated. For instance, despite the fact that Muslims and Jews worshiped the same God and shared much of the same sacred literature, medieval Europeans had absolutely no qualms about invading Muslim lands and committing horrific atrocities in the name of their religion. Likewise, medieval anti-Semitism (prejudice and hatred directed against Jews) eventually drove many Jews from Europe itself to take shelter in the kingdoms and empires of the Middle East and North Africa. Historically it was much safer and more comfortable for Jews in places like the predominantly Muslim Ottoman Empire than it was in most of Christian Europe.

A major irony of the idea that Western Civilization is somehow inherently Christian is that Islam is unquestionably just as “Western.” Islam’s point of origin, the Arabian Peninsula, is geographically very close to that of both Judaism and Christianity. Its holy writings are also closely aligned to Jewish and Christian values and thought. Perhaps most importantly, Islamic kingdoms and empires were part of the networks of trade, scholarship, and exchange that linked together the entire greater Mediterranean region. Thus, despite the fervor of European crusaders, it would be profoundly misleading to separate Islamic states and cultures from the rest of Western Civilization.

Perhaps the most crucial development in the idea of Western Civilization in the pre-modern period was the Renaissance. The idea of the “Middle Ages” was invented by thinkers during the Renaissance, which started around 1300 CE. The great thinkers and artists of the Renaissance claimed to be moving away from the ignorance and darkness of the Middle Ages – which they also described as the “dark ages” – and returning to the greatness of the Romans and Greeks. People like Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Christine de Pizan, and Petrarch proudly connected their work to the work of the Romans and Greeks, claiming that there was an unbroken chain of ideas, virtues, and accomplishments stretching all the way back thousands of years to people like Alexander the Great, Plato, and Socrates.

During the Renaissance, educated people in Europe roughly two thousand years after the life of the Greek philosopher Plato based their own philosophies and outlooks on Plato’s philosophy, as well as that of other Greek thinkers. The beauty of Renaissance art is directly connected to its inspiration in Roman and Greek art. The scientific discoveries of the Renaissance were inspired by the same spirit of inquiry that Greek scientists and Roman engineers had cultivated. Perhaps most importantly, Renaissance thinkers proudly linked together their own era to that of the Greeks and Romans, thus strengthening the concept of Western Civilization as an ongoing enterprise.

In the process of reviving the ideas of the Greeks and Romans, Renaissance thinkers created a new program of education: “humanist” education. Celebrating the inherent goodness and potentialities of humankind, humanistic education saw in the study of classical literature a source of inspiration for not just knowledge, but of morality and virtue. Combining the practical study of languages, history, mathematics, and rhetoric (among other subjects) with the cultivation of an ethical code the humanistics traced back to the Greeks, humanistic education ultimately created a curriculum meant to create well-rounded, virtuous individuals. That program of education remained intact into the twentieth century, with the study of the classics remaining a hallmark of elite education until it began to be displaced by the more specialized disciplinary studies of the modern university system that was born near the end of the nineteenth century.

It was not Renaissance ideas, however, that had the greatest impact on the globe at the time. Instead, it was European soldiers, colonists, and most consequentially, diseases. The first people from the Eastern Hemisphere since prehistory to travel to the Western Hemisphere (and remain – an earlier Viking colony did not survive) were European explorers who, entirely by accident, “discovered” the Americas at the end of the fifteenth century CE. It bears emphasis that the “discovery” of the Americas is a misnomer: millions of people already lived there, as their ancestors had for thousands of years, but geography had left them ill-prepared for the arrival of the newcomers. With the European colonists came an onslaught of epidemics to which the Native peoples of the Americas had no resistance, and within a few generations the immense majority – perhaps as many as 90% – of Native Americans perished as a result. The subsequent conquest of the Americas by Europeans and their descendents was thus made vastly easier. Europeans suddenly had access to an astonishing wealth of land and natural resources, wealth that they extracted in large part by enslaving millions of Native Americans and Africans.

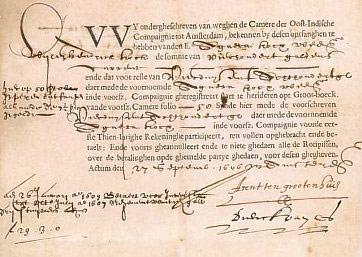

Thanks largely to the European conquest of the Americas and the exploitation of its resources and its people, Europe went from a region of little economic and military power and importance to one of the most formidable in the following centuries. Following the Spanish and Portuguese conquest of Central and South America, the other major European states embarked on their own imperialistic ventures in the following centuries. “Trade empires” emerged over the course of the seventeenth century, first and foremost those of the Dutch and English, which established the precedent that profit and territorial control were mutually reinforcing priorities for European states. Driven by that conjoined motive, European states established huge, and growing, global empires. By 1800, roughly 35% of the surface of the world was controlled by Europeans or their descendants.

Most of the world, however, was off limits to large-scale European expansion. Not only were there prosperous and sophisticated kingdoms in many regions of Africa, but (in an ironic reversal of the impact of European diseases on Americans) African diseases ensured that would-be European explorers and conquerors were unable to penetrate beyond the coasts of most of sub-Saharan African entirely. Meanwhile, the enormous and sophisticated empires and kingdoms of China, Japan, Southeast Asia, and South Asia (i.e. India) largely regarded Europeans as incidental trading partners of relatively little importance. The Middle East was dominated by two powerful and “western” empires of its own: Persia and the Ottoman Empire.

The explosion of European power, one that coincided with the fruition of the idea that Western Civilization was both distinct from and better than other branches of civilization, came as a result of a development in technology: the Industrial Revolution. Starting in Great Britain in the middle of the eighteenth century, Europeans learned how to exploit fossil fuels in the form of coal to harness hitherto unimaginable amounts of energy. That energy underwrote a vast and dramatic expansion of European technology, wealth, and military power, this time built on the backs not of outright slaves, but of workers paid subsistence wages.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution underwrote and enabled the transformation of Europe from regional powerhouse to global hegemon. By the early twentieth century, Europe and the American nations founded by the descendents of Europeans controlled roughly 85% of the globe. Europeans either forced foreign states to concede to their economic demands and political influence, as in China and the Ottoman Empire, or simply conquered and controlled regions directly, as in South Asia (i.e. India) and Africa. None of this would have been possible without the technological and energetic revolution wrought by industrialism.

To Europeans and North Americans, however, the reason that they had come to enjoy such wealth and power was not because of a (temporary) monopoly of industrial technology. Instead, it was the inevitable result of their inherent biological and cultural superiority. The idea that the human species was divided into biologically distinct races was not entirely invented in the nineteenth century, but it became the predominant outlook and acquired all the trappings of a “science” over the course of the 1800s. By the year 1900, almost any person of European descent would have claimed to be part of a distinct, superior “race” whose global dominance was simply part of their collective birthright.

That conceit arrived at its zenith in the first half of the twentieth century. The European powers themselves fell upon one another in the First World War in the name of expanding, or at least preserving, their share of global dominance. Soon after, the new (related) ideologies of fascism and Nazism put racial superiority at the very center of their worldviews. The Second World War was the direct result of those ideologies, when racial warfare was unleashed for the first time not just on members of races Europeans had already classified as “inferior,” but on European ethnicities that fascists and Nazis now considered inferior races in their own right, most obviously the Jews. The bloodbath that followed resulted in approximately 55 million deaths, including the 6 million Jewish victims of the Holocaust and at least 25 million citizens of the Soviet Union, another “racial” enemy from the perspective of the Nazis.

It was against the backdrop of this descent into what Europeans and Americans frequently called “barbarism” – the old antithesis of the “true” civilization that started with the Greeks – that the history of Western Civilization first came into being as a textbook topic and, soon, a mainstay of college curriculums. Prominent scholars in the United States, especially historians, came to believe that the best way to defend the elements of civilization with which they most strongly identified, including certain concepts of rationality and political equality, was to describe all of human existence as an ascent from primitive savagery into enlightenment, an ascent that may not have strictly speaking started in Europe, but which enjoyed its greatest success there. The early proponents of the “Western Civ” concept spoke and wrote explicitly of European civilization as an unbroken ladder of ideas, technologies, and cultural achievements that led to the present. Along the way, of course, they included the United States as both a product of those European achievements and, in the twentieth century, as one of the staunchest defenders of that legacy.

That first generation of historians of Western Civilization succeeded in crafting what was to be the core of history curriculums for most of the twentieth century in American colleges and universities, not to mention high schools. The narrative in the introduction in this book follows its basic contours, without all of the qualifying remarks: it starts with Greece, goes through Rome, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, then on to the growth in European power leading up to the recent past. The traditional story made a hard and fast distinction between Western Civilization as the site of progress, and the rest of the world (usually referred to as the “Orient,” simply meaning “east,” all the way up until textbooks started changing their terms in the 1980s) which invariably lagged behind. Outside of the West, went the narrative, there was despotism, stagnation, and corruption, so it was almost inevitable that the West would eventually achieve global dominance.

This was, in hindsight, a somewhat surprising conclusion given when the narrative was invented. The West’s self-understanding as the most “civilized” culture had imploded with the world wars, but the inventors of Western Civilization as a concept were determined to not only rescue its legacy from that implosion, but to celebrate it as the only major historical legacy of relevance to the present. In doing so, they reinforced many of the intellectual dividing lines created centuries earlier: there was true civilization opposed by barbarians, there was an ongoing and unbroken legacy of achievement and progress, and most importantly, only people who were born in or descended from people born in Europe had played a significant historical role. The entire history of most of humankind was not just irrelevant to the narrative of European or American history, it was irrelevant to the history of the modern world for everyone. In other words, even Africans and Asians, to say nothing of the people of the Pacific or Native Americans, could have little of relevance to learn from their own history that was not somehow “obsolete” in the modern era. And yet, this astonishing conclusion was born from a culture that unleashed the most horrific destruction (self-destruction) ever witnessed by the human species.

This textbook follows the contours of the basic Western Civilization narrative described above in terms of chronology and, to an extent, geography because it was written to be compatible with most Western Civilization courses as they exist today. It deliberately breaks, however, from the “triumphalist” narrative that describes Western Civilization as the most successful, rational, and enlightened form of civilization in human history. It casts a wider geographical view than do traditional Western Civilization textbooks, focusing in many cases on the critical historical role of the Middle East, not just Europe. It also abandons the pretense that the history of Western Civilization was generally progressive, with the conditions of life and understanding of the natural world of most people improving over time (as a matter of fact, they did not).

The purpose of this approach is not to disparage the genuine breakthroughs, accomplishments, and forms of “progress” that did originate in “the West.” Technologies as diverse and important as the steam engine and antibiotics originated in the West. Major intellectual and ideological movements calling for religious toleration, equality before the law, and feminism all came into being in the West. For better and for worse, the West was also the point of origin of true globalization (starting with the European contact with the Americas, as noted above). It would be as misleading to dismiss the history of Western Civilization as unimportant as it is to claim that only the history of Western Civilization is important.

Thus, this textbook attempts to present a balanced account of major events that occurred in the West over approximately the last 10,000 years. “Balance” is in the eye of the reader, however, so the account will not be satisfactory to many. The purpose of this introduction is to make explicit the background and the framework that informed the writing of the book, and the author chooses to release it as an Open Education Resource in the knowledge that many others will have the opportunity to modify it as they see fit.

Finally, a note on the kind of history this textbook covers is in order. For the sake of clarity and manageability, historians distinguish between different areas of historical study: political, intellectual, military, cultural, artistic, social, and so on. Historians have made enormous strides in the last sixty years in addressing various areas that were traditionally neglected, most importantly in considering the histories of the people who were not in power, including the common people of various epochs, of women for almost all of history, and of slaves and servants. The old adage that “history is written by the winners” is simply untrue – history has left behind mountains of evidence about the lives of those who had access to less personal autonomy than did social elites. Those elites did much to author some of the most familiar historical narratives, but those traditional narratives have been under sustained critique for several decades.

This textbook tries to address at least some of those histories, but here it will be found wanting by many. Given the vast breadth of history covered in its chapters, the bulk of the consideration is on “high level” political history, charting a chronological framework of major states, political events, and political changes. There are two reasons for that approach. First, the history of politics lends itself to a history of events linked together by causality: first something happened, and then something else happened because of it. In turn, there is a fundamental coherence and simplicity to textbook narratives of political history (one that infuriates many professional historians, who are trained to identify and study complexity). Political history can thus serve as an accessible starting place for newcomers to the study of history, providing a relatively easy-to-follow chronological framework.

The other, related, reason for the political framing of this textbook is that history has long since declined as a subject central to education from the elementary through high school levels in many parts of the United States. It is no longer possible to assume that anyone who has completed high school already has some idea of major (measured by their impact at the time and since) events of the past. This textbook attempts to use political history as, again, a starting point in considering events, people, movements, and ideas that changed the world at the time and continue to exert an influence in the present.

To be clear, not all of what follows has to do with politics in so many words. Considerable attention is also given to intellectual, economic, and to an extent, religious history. Social and cultural history are covered in less detail, both for reasons of space and the simple fact that the author was trained as an intellectual historian interested in political theory. These, hopefully, are areas that will be addressed in future revisions.

Original Version: March 2019

The second edition of this textbook attempts to redress some of the “missing pieces” noted in the conclusion of the introduction above. First, greater emphasis is placed on the history of the Middle East, especially in the period after the collapse of the political authority of the Abbasid Caliphate in the ninth century CE. The textbook now addresses the histories of Persia (Iran) and the Ottoman Empire in considerable detail, emphasizing both their own political, religious, and economic developments and their respective relationships with other cultures. Second, much greater focus is given to the history of gender roles and to women’s history.

From the perspective of the author, the new material on the Middle East integrates naturally with the narrative because it remains focused mostly on political history. The material on gender and women’s history requires a shift in the overall approach of the textbook in that women were almost entirely excluded from traditional “high-level” political histories precisely because so few women were ever in positions of political authority until the recent past. The shift in focus to include more women’s history necessarily entails greater emphasis not just on gender roles, but on the social history of everyday life, stepping away at times from the political history framework of the volumes as a whole. The result is a broader and more robust historical account than that of the earlier edition, although the overarching narrative is still driven by political developments.

Finally, a note on grammatical conventions: in keeping with most American English approaches, the writing errs on the side of capitalizing proper nouns. For example, terms like “the Church” when referring to the Catholic Church in its institutional presence, specific regions like “Western Europe,” and historical eras like “the Middle Ages” and “the Enlightenment” are all capitalized. When possible, the names of individuals are kept as close to their authentic spelling and/or pronunciation as possible, hence “Chinggis Khan” instead of “Genghis Khan,” “Wilhelm I” instead of “William I,” and “Nikolai I” instead of “Nicholas I.” Some exceptions have been made to avoid confusion where there is a prevailing English version, as in “Joseph Stalin” instead of the more accurate “Iosif Stalin.” Diacritical marks are kept when possible in original spellings, as in the term “Führer” when discussing Adolf Hitler. Herculean efforts have gone into reducing the number of semicolons throughout the text, to little avail.

Dr. Christopher Brooks

Faculty Member in History, Portland Community College

Second Edition: February 2020

This chapter contains a remix of text from the following:

The main text is taken from Christopher Brooks, “Introduction” in Western Civilization: A Concise History, Volume 1, by Christopher Brooks licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 International License.

An introductory paragraph by Nicole V. Jobin was added. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

By 1560, Europe was divided by religion as it had never been before. Protestantism was now a permanent feature of the landscape of beliefs and even the most optimistic Catholics had to abandon hopes that they could win many Protestants back over to the Roman Church through propaganda and evangelism. A patchwork of peace treaties across most of Europe had established the principle of princes determining the acceptable religion within their respective territories, but those treaties in no way represented something recognizable today as “tolerance” – in fact, all sides believed they had exclusive access to spiritual truth. Simply put, the very notion of tolerance, of “live and let live,” was almost nonexistent in early-modern Europe. Exceptions did exist, especially in the Holy Roman Empire, but beliefs clearly hardened over the course of the sixteenth century: what tolerance had existed in the early decades of the Reformation era tended to fade away.

This was not just about Catholic intolerance. While the Catholic Inquisition is an iconic institution in the history of persecution, most Protestants were equally hostile to Catholics. This was especially true among Huguenots in France, who aggressively proselytized and who imposed harsh social and, if they could, legal controls of behavior in their areas of influence, which included various towns in southern France, not just Switzerland. In addition, while actual wars between Protestant sects were rare (the English Civil War of the sixteenth century being something of an exception), different Protestant groups usually detested one another.

Why was religion so divisive? It was more than just incompatible belief systems, with some of the reasons being very specific to the early modern period. First, religion was “owned” by princes. A given territory’s religion was deeply connected to the faith of its leader. Princes often held some authority in church lands, and priests had always served as important royal officials. There were also numerous ecclesiastical territories, especially in the Holy Roman Empire, that were wholly controlled by “princes of the church.” Likewise, only states had the resources to reform whole institutions, replacing seminaries, universities, libraries, and so on with new material in the case of Protestant states. This necessitated an even closer relationship between church and state. In turn, an individual’s religious confession was concomitant with loyalty or disloyalty to her prince – someone following a rival branch of Christianity was, from the perspective of a ruler, not just a religious dissenter, but a political rebel.

At the same time, over the course of the sixteenth century, specific, hardened doctrines of belief were nailed down by the competing confessions. The Lutherans published a specific creed defining Lutheran beliefs known as the Augsburg Confession in 1530, and the Catholic Council of Trent in the following decades defined exactly what Catholic doctrine consisted of. There was thus a hardening of beliefs as ambiguities and points of common agreement were eliminated.

Terms for Identification

Religion was thus more than sufficient as a cause of conflict in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. As it happens, however, there was another major cause of conflict, one that lent to the savagery of many of the religious wars of the period: the Little Ice Age. A naturally occurring fluctuation in the earth’s climate saw the average temperature drop by a few degrees during the period, enhancing the frequency and severity of bad harvests. In the Northern Hemisphere, that change began in the fourteenth century but became dramatically more pronounced between 1570 and the early 1700s, with the single most severe period lasting from approximately 1600 until 1640, precisely when the most destructive religious war of all raged in Europe, the Thirty Years’ War that devastated the Holy Roman Empire.

Overlay of different historical reconstructions of average temperatures over the last two thousand years. Temperatures continue to climb rapidly in the present era.

Lower temperatures meant that crop yields were lower, outright crop failures more common, and famines more frequent. In societies that were completely dependent on agriculture for their very survival, these conditions ensured that social and political stability was severely undermined. To cite just one example, the price of grain increased by 630% in England over the course of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, driving peasants on the edge of subsistence to even greater desperation. Indeed, historians have now demonstrated that not just Europe, but major states across the world from Ming China, to the Ottoman Empire, to European colonial regimes in the Americas all suffered civil wars, invasions, or religious conflicts at this time, and that climate was a major causal factor. Historians now refer to a “general crisis of the seventeenth century” in addressing this phenomenon.

Thus, religious conflict overlapped with economic crisis, with the latter making the former even more desperate and bloody. The results are reflected in some simple statistics: from 1500 to 1700, some part of Europe was at war 90% of the time. There were only four years of peace in the entire seventeenth century. The single most powerful dynasty, the Habsburgs, were at war two-thirds of the time during this period.

Discussion Questions

Against this backdrop of crisis, the first major religious wars of the period were in France. France was, next to Spain, one of the most powerful kingdoms in Europe. It was the most populous and had large armies. It had a dynamic economy and significant towns and cities. It also had a very weak monarchy under the ruling Valois dynasty, which was kept in check by the powerful nobility.

The Reformation launched by Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) in 1517 had reached France by 1521 but was not as enthusiastically received as it had been in the Germanic territories of the Holy Roman Empire where Luther and his followers were at work. Francois I, a devout Catholic, became king in 1515 but refrained from persecuting Protestant activists mainly because of his sister, Marguerite de Navarre (l. 1492-1549), who was sympathetic to the cause and used her position as Queen of Navarre and influence over Francois I to protect them. Marguerite also intervened to reduce tensions by mediating between Catholics and Protestants to keep the peace.

Tensions between the two factions were present but controlled until October 17-18, 1534, when placards denouncing the Catholic Mass were publicly posted in Blois, Orleans, Paris, Rouen, and Tours – with one even appearing on the door of Francois I’s bedroom. Although this event, known as the Affair of the Placards, has been traditionally attributed to the Protestant Reformer Antoine Marcourt, some scholars believe it may have been organized by conservative Catholic authorities who had grown tired of Francois I’s leniency toward what they considered heresy and wanted to force him to act.

Francois I did so by initiating the persecution of Protestants and ignoring his sister’s pleas for restraint. Many Protestants, including Reformer John Calvin (l. 1509-1564), left France at this time but those who remained were prohibited from gathering, preaching, or even casually discussing their views. Persecution under Francois I culminated in the Massacre of Merindol in 1545 in which thousands of the heretical sect of the Waldensians, who supported reform, were slaughtered and the survivors arrested and enslaved.

Francois I died in 1547 and was succeeded by his son Henry II who continued his policies. There was no restraining influence over Henry, as Marguerite de Navarre had been with Francois I, but his persecutions only drove Protestantism underground where it took hold and gained further support, even among members of the noble class such as Louis de Bourbon, Prince of Conde (l. 1530-1569) and Jeanne d’Albret (l. 1528-1572), daughter of Marguerite de Navarre, and Queen of Navarre after 1555.

The religious and political situation worsened after Henry II (r. 1547-1559) died from an injury. His son, Francois II (Francis II, r. 1559-1560), crowned king at the age of 15, had been married to Mary, Queen of Scots (l. 1542-1587) who was the niece of Francis, Duke of Guise (l. 1519-1563) and his brother Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine (l. 1524-1574). Although Francis II was of age to rule on his own, his mother, Catherine de ‘Medici (l. 1519-1589) encouraged the Guise brothers to assume control as Francis II was inexperienced and sickly. The Guise brothers quickly isolated the king from others at court.

The House of Guise, devoutly Catholic, then exercised the power behind the throne and was hostile to the efforts of the Huguenots (French Protestants) who were advancing their vision in France. In March 1560, a group of Huguenots tried to kidnap Francis II to remove him from the influence of the Guise brothers. The plot, known as the Amboise Conspiracy, was discovered and anyone thought to be involved, as well as over 1,000 other Huguenots, were executed. In retaliation, Huguenots began vandalizing Catholic churches and rising tensions led to the Massacre of Vassy in March of 1562, in which Catholics killed more Protestants, starting the first war. Francis II died in 1560 and was replaced by his brother Charles IX who was only nine years old. His mother Catherine acted as regent until 1563 when the Parlement of Roun declared him of age.

France was thus divided between two major factions, led by the fanatically Catholic Guise family and the Huguenot Bourbon family. The former was advised by the Jesuits and supported by the king of Spain, while the latter represented the growing numbers of economically dynamic Huguenots concentrated in the south (they were especially numerous in Navarre, a small independent kingdom between France and Spain that was soon embroiled in the war). As of 1560 fully 10% of the people of France were Huguenots, many of whom represented its dynamic middle class: merchants, lawyers, and prosperous townsfolk. In addition, between one-third and one-half of the lower nobility were Huguenots, so the Huguenots as a group were more powerful than their numbers might initially indicate. Fearing the power of the Huguenots and detesting their faith, the Guises created the Catholic League, an armed militia of Catholics that included armed monks, townsfolk, and soldiers.

From 1562 to 1572 there was on-again, off-again fighting between the Catholic League and Huguenot forces. Catherine de Medici tended to vacillate between supporting her fellow Catholics and supporting Protestants who were the enemies of Spain, France’s rival to the south. Despite their own professed Catholicism, neither Charles nor Catherine were fanatical in their religious outlook, much to the frustration of the nobles of the Catholic League.

Hoping to end the conflict, Charles and Catherine invited the Huguenot Prince Henry of Navarre, leader of the Protestant forces, to Paris in 1572 to marry Charles’ sister Margaret. Henry arrived in Paris with some 2,000 Huguenot followers, all of whom had agreed to arrive unarmed. The Duke of Guise led a conspiracy, however, to convince the king that only the death of Henry and his followers would truly end the threat of religious division, and with the king’s approval, Catholic forces launched a massacre on St. Bartholomew’s Day, August 24, in which more than 2,000 Protestants were killed. That day, the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, would live in infamy in French history as a stark example of religiously-fueled hatred.

A gruesome depiction of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre painted by a Huguenot.

The events in Paris, in turn, sparked massacres all over the country with at least 20,000 more deaths (supposedly, the pope was so pleased with the news that he gave 100 gold coins to the messenger who brought it to him). The one important person who survived was the leader of the Huguenot cause, Henry of Navarre, who half-heartedly “converted” to Catholicism to ensure his safety but then escaped to the south and rallied the Huguenot resistance. Charles died in 1574 of an illness, leaving his younger brother Henry III as the last male member of his family line available for the throne. After a lull in the fighting, the war resumed in 1576.

In the years that followed, the French Wars of Religion turned into a three-way civil war pitting the Catholic League against the legitimate king of France (both sides were Catholic, but as focused on destroying each other as they were fighting Huguenots) with the Huguenots fighting both in turn. There was almost a macabre humor to the fact that the leaders of the three factions were all named Henry – King Henry III of Valois, Prince Henry IV of Navarre, and the leader of the Catholic League, Henry, Duke of Guise. The protestants appealed to England and the protestant German princes for aid, the Catholic factions sought the support of Spain. Further assassinations followed, including those of both the Duke of Guise (d. 1588), killed by King Henry III’s guards, and the king himself (d. 1589), killed by a fanatical Dominican friar in retaliation. On his deathbed, Henry III named Henry of Navarre his heir and begged him, for the sake of the kingdom, to convert. After more battles with the Catholic League, he came to agree that he would have to convert in order to rule Catholic France. He supposedly said that “Paris vaut bien un messe” (Paris is well worth a Mass). He was formally received into the Catholic Church in 1593 and after a climactic battle in 1594, he was crowned at Chartres and declared Henry IV, King of France.

Henry IV went on to become popular among both Catholics and Protestants for his competence, wit, and pragmatism. In 1598 he issued the Edict of Nantes that officially propagated toleration to the Huguenots, allowing them to build a parallel state within France with walled towns, armies, and an official Huguenots church, but banning them from Paris and participation in the royal government. He was eventually assassinated (after eighteen previous attempts) in 1610 by a Catholic fanatic, but by his death the pragmatic necessity of tolerance was accepted even by most French Catholics. Ultimately, the “solution” to the French Wars of Religion ended up being political unity instead of religious unity, a conclusion reached out of pure pragmatism rather than any kind of heartfelt toleration of difference.

French War of Religion Timeline

1534 Affair of the Placards

1562-1598 Off and on again wars between Catholic and Protestant Factions

1572 St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre

1593 Henry of Navarre converts to Catholicism to gain the throne of France

1594 Henry of Navarre crowned King of France

1598 Edict of Nantes grants religious liberties to Huguenots

Following Henry IV’s victory, the royal line of the Bourbons would rule France until the French Revolution that began in 1789. The Bourbons’ greatest rivals for most of that period were the Habsburg royal line, who possessed the Austrian Empire, were the nominal heads of the Holy Roman Empire, and by the sixteenth century had control of Spain and its enormous colonial empire as well.

The Spanish king in the mid-sixteenth century was Philip II (r. 1556 – 1598), son of the former Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Philip regarded his place in Europe, and history, as being the most staunch defender of Catholicism possible. This translated to harsh, even tyrannical, suspicion and persecution of not only non-Catholics, but those Catholics suspected of harboring secret non-Catholic beliefs. He viciously persecuted the Moriscos, the converted descendants of Spanish Muslims, and forced them to turn their children over to Catholic schools for education. He also held the Conversos, converted descendants of Spanish Jews, as suspect of secretly continuing to practice Judaism, with the Spanish Inquisition frequently trying Conversos on suspicion of heresy.

Philip was able to exercise a great deal of control over Spanish society. He had much more trouble, however, in imposing similar control and religious unity in his foreign possessions, most importantly the Netherlands, a collection of territories in northern Europe that he had inherited from his various royal ancestors. The Netherlands was an amalgam of seventeen provinces with a diverse society and religious denominations, all held in a delicate balance. It was also rich, boasting significant overseas and European commercial interests, all led by a dynamic merchant class. In 1566, Spanish interference in Dutch affairs led to Calvinist attacks on Catholic churches, which in turn led Philip to send troops and the Inquisition to impose harsher control. The most notorious person in this effort was the Spanish Duke of Alba, who sat at the head of a military court called the Council of Troubles, but known to the Dutch as the Council of Blood. Alba executed those even suspected of being Protestants, which accomplished little more than rallying Dutch resistance.

A Dutch Prince, William the Silent (1533 – 1584), led counter-attacks against Spanish forces, and the duke was recalled to Spain in 1573. Spanish troops, however, were no longer getting paid regularly by the crown and revolted, sacking several Dutch cities that had been loyal to Spain, including Brussels, Ghent, and especially Antwerp. These attacks were described as the “Spanish fury” by the Dutch, and they not only permanently undermined the economy of the cities that were sacked, they lent enormous fuel to the Dutch Revolt itself.

The Spanish Fury.

In 1581 the northern provinces declared their independence from Spain. In 1588 they organized as a republic led by wealthy merchants and nobles. Flooded with Calvinist refugees from the south, the Dutch Republic became staunchly Protestant and a strong ally of Anglican England. Spain, in turn, maintained an ongoing and enormously costly military campaign against the Republic until 1648. The supply train for Spanish armies, known as the Spanish Road, stretched all the way from Spain across west-central Europe, crossing over both Habsburg territories and those controlled by other princes. It was hugely costly; despite the enormous ongoing shipments of bullion from the New World, the Spanish monarchy was wracked by debts, many of which were due to the Dutch conflict.

Even as Spain found itself mired in an ongoing and costly conflict in the Netherlands, hostility developed between Spain and England. Philip married the English queen Mary Tudor in part to try to bring England back to Catholicism after Mary’s father Henry VIII had broken with the Roman Church and created the Church of England. Mary and Philip persecuted Anglicans, but Mary died after only five years (r. 1553 – 1558) without an heir. Her sister, Elizabeth, refused Philip’s proposal of marriage and rallied to the Anglican cause. As hostility between England and Spain grew, Elizabeth’s government sponsored privateers – pirates working for the English crown – led by a skillful and ruthless captain named Sir Francis Drake. These privateers began a campaign of raids against Spanish possessions in the New World and even against Spanish ports, culminating in the sinking of an anchored Spanish fleet in Cadiz in 1587. Simultaneously, the English supported the Dutch Protestant rebels who were engaged in the growing war against Spain. Infuriated, Philip planned a huge invasion of England.

This conflict reached a head in 1588. Philip spent years building up an enormous fleet known as the Spanish Armada of 132 warships, equipped not only with cannons but designed to carry thousands of soldiers to invade England. It sailed in 1588, but was resoundingly defeated by a smaller English fleet in a sea battle in the English Channel. The English ships were smaller and more maneuverable, their cannons were faster and easier to reload, and English captains knew how to navigate in the fickle winds of the Channel more easily than did their Spanish counterparts, all of which spelled disaster for the Spanish fleet. The Armada was forced to limp around England, Scotland, and Ireland trying to get back to Spain, finally returning having lost half of its ships and thousands of men. The debacle conclusively ended Spain’s attempt to invade England and eliminated the threat to the Anglican church.

The end result of the foreign wars that Spain waged in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was simple: bankruptcy. Despite the enormous wealth that flowed in from the Americas, Spain went from being the single greatest power in Europe as of about 1550 to a second-tier power by 1700. Never again would Spain play a dominant role in European politics, although it remained in possession of an enormous overseas empire until the early nineteenth century.

The most devastating religious conflict in European history happened in the middle of the Holy Roman Empire. It ultimately dragged on for decades and saw a reduction of the population in the German Lands of between 20 – 40%. That conflict, the Thirty Years’ War, saw the most horrific acts of violence, the greatest loss of life, and the greatest suffering among both soldiers and civilians of any of the religious wars of the period.

Leading up to the outbreak of war, there was an uneasy truce in the Holy Roman Empire between the Catholic emperor, who had limited power outside of his own ancestral (Habsburg) lands, and the numerous Protestant princes in their respective, mostly northern, territories. As of 1618, that compromise had held since the middle of the sixteenth century and seemed relatively stable, despite the religiously-fueled wars across the borders in France and the Netherlands.

The compromise fell apart because of a specific incident, the attempted murder of two Catholic imperial officials by Protestant nobles in Prague, when the emperor Ferdinand II attempted to crack down on Protestants in Bohemia (corresponding to the present-day Czech Republic). Ferdinand sent officials to Prague to demand that Bohemia as a whole renounce Protestantism and convert to Catholicism. The Bohemian Diet, the local parliament of nobles, refused and threw the two officials out of the window of the building in which they were meeting; that event came to be known as the Defenestration of Prague (“defenestration” literally means “un-windowing”).

The Diet renounced its allegiance to the emperor and pledged to support a Protestant prince instead. A flurry of attacks and counter-attacks ensued, ultimately pitting the Catholic Habsburgs against the German Protestant princes and, soon, their allied Danish king. The Habsburgs led a Catholic League, supported by powerful Catholic princes, while Frederick of the Palatinate, a German Calvinist prince, led the Protestant League against the forces of the emperor.

From 1620 – 1629, Catholic forces won a series of major victories against the Protestants. Bohemia itself was conquered by Catholic forces and over 100,000 Protestants fled; during the course of the war Bohemia lost 50% of its population. Catholic armies were particularly savage in the conflict, living off the land and slaughtering those who opposed them. The Danish king, Christian IV, entered the war in 1625 to bolster the Protestant cause, but his armies were crushed and Denmark was briefly occupied by the Catholic forces. This period of Catholic triumph saw the Emperor Ferdinand II issue an Edict of Restitution in 1629 that demanded the return of all Church lands seized since the Reformation – this was hugely disruptive, as those lands had been in the hands of different states for over 80 years at that point!

In 1630, the Swedish king, Gustavus Adolphus, received financial backing from the French to oppose the Habsburgs and their forces. Under the leadership of its savvy royal minister, Cardinal Richelieu, France worked to hold its Habsburg rivals in check despite the shared Catholicism of the French and Habsburg states. Adolphus invaded northern Germany in 1630, then won a major victory against the Catholic forces in 1631. He went on to lead a huge Protestant army through the Empire, reversing Catholic gains everywhere and exacting the same kind of brutal treatment against Catholics as had been inflicted on Protestants. In 1632, Adolphus died in battle and the military leader of the Catholics, a nobleman named Wallenstein, was assassinated, leaving the war in an ongoing, bloody stalemate.

In 1635 the French entered the war on the Protestant side. At this point, the war shifted in focus from a religious conflict to a dynastic struggle between the two greatest royal houses of Europe: the Bourbons of France and the Habsburgs of Austria. It also extended well beyond Germany: follow-up wars were fought between France and Spain even after the 30 Years’ War itself ended in 1648, and Spain provided both troops and financial support to the Habsburg forces in Germany as well.

For the next thirteen years, from the French intervention in 1635 until the war finally ended in 1648, armies battled their way across the Empire, funded by the various elite states and families of Europe but exacting a terrible toll on the German lands and people. From 1618 – 1648, the population of the Empire dropped by 8,000,000. Whole regions were depopulated and massive tracts of farmland were rendered barren; it took until close to 1700 for the Empire to begin to recover economically. In 1648, exhausted and deeply in debt, both sides finally met to negotiate a peace. The result was the Treaty of Westphalia, which was negotiated by a series of messages sent back and forth between the two sides, since the delegations refused to be in the same town.

The end result was that the already-weak centralized power of the Holy Roman Empire was further reduced, with the constituent states now enjoying almost total autonomy. In terms of the religious map of the Empire, there was one major change, however: despite the fact that the Catholic side had not “won” the war per se, Catholicism itself did benefit from the early success of the Habsburgs. Whereas roughly half of Western and Central Europe was Protestant in 1590, only one-fifth of it was in 1690; that was in large part because few people remained Protestants in Habsburg lands after the war.

The “winners” of the war were really the relatively centralized kingdoms of France and Sweden, with Austria’s status as the most powerful individual German state also confirmed. The big loser was Spain: having paid for many of the Catholic armies for thirty years, it was essentially bankrupt, and its monarchy could not reorganize in a more efficient manner as did its French rivals. Likewise, Spain missed out on the subsequent economic expansion of Western Europe; the war had undermined the economy of Central Europe, and the center of economic dynamism thus shifted to the Atlantic seaboard, especially France, England, and the Netherlands. There, a mercantile middle class became more important than ever, while Spain remained tied to its older agricultural and bullion-based economic system.

If the war had a positive effect, it was that it spelled the end of large-scale religious conflict in Europe. There would be harsh, and official, intolerance well into the nineteenth century, but even pious monarchs were now very hesitant to initiate or participate in full-scale war in the name of religious belief. Instead, there was a kind of reluctant, pragmatic tolerance that took root across all of Europe – the same kind of tolerance that had emerged in France half a century earlier at the conclusion of the French Wars of Religion.

Soldiers robbing, murdering, and raping peasants during the War. The conduct of soldiers was so horrific that many Europe elites came to believe that better-regulated and led armies were essential to prevent chaos in the future.

Perhaps the most important change that took place in the aftermath of the wars was that European elites came to focus as much on the way wars were fought as the reasons for war. The conduct of rapacious soldiers had been so atrocious in the wars, especially in the Holy Roman Empire, that many states went about the long, difficult process of creating professional standing armies that reported to noble officers, rather than simply hiring mercenaries and letting them run amok.

The Thirty Years War

1618 Defenestration of Prague

1618-1620 Bohemian Revolt against Catholic Habsburg rule

1625-1629 Denmark’s Engagement in the war on the Protestant side

1630-1634 Sweden’s Engagement in the war led by King Gustavus Adolphus

1635-1648 France switches support from the Habsburgs to the Protestants

1648 Peace of Westphalia ends the Thirty Year’s War

Obviously, neither Catholics nor Protestants “won” the wars of religion that wracked Europe from roughly 1550 – 1650. Instead, millions died, intolerance remained the rule, and the major states of Europe emerged more focused than ever on centralization and military power. If there was a silver lining, it was that rulers did their best to clamp down on explosions of religiously-inspired violence in the future, in the name of maintaining order and control. Those concepts – order and control – would go on to inspire the development of a new kind of political system in which kings would claim almost total authority: absolutism.

Discussion Questions:

Little Ice Age – Robert A. Rohde

St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre – Public Domain

The Spanish Fury – Public Domain

Marauding Soldiers – Public Domain

The Peace of Westphalia and Sovereignty from Lumen Learning – Western Civilization

The 17th Century Crisis: Crash Course European History #11

St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre by Joshua j. Mark at the World History Encyclopedia site

Shaping History: Ordinary People in European Politics, 1500-1700. “Ch. 4: The Political Crisis of the Seventeenth Century” by Wayne te Brake. (Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998). http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft500006j4/

This chapter contains a remix of text from the following:

The main text is taken from Christopher Brooks, “Chapter 7: Religious Wars,” in Western Civilization: A Concise History Volume 2, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Text from Joshua J. Marks, “French Wars of Religion.” in the World History Encyclopedia, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License was added to the section on the French Wars of Religion.

Original material in the text boxes and the inclusion of a “For Further References” section by Nicole V. Jobin, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

“Absolutism” is a concept of political authority created by historians to describe a shift in the governments of the major monarchies of Europe in the early modern period. In other words, while the monarchs of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries certainly knew they were doing something differently than had their predecessors, they did not use the term “absolutism” itself. The central idea behind absolutism was that the king or queen was, first, the holder of (theoretically) absolute political power within the kingdom, and second, that the monarch’s every action should be in the name of preserving and guaranteeing the rights and privileges of his or her subjects, occasionally even including the peasants.

Absolutism was in contrast to medieval and Renaissance-era forms of monarchy in which the king was merely first among equals, holding formal feudal authority over his elite nobles, but often being merely their equal, or even inferior, in terms of real authority and power. As demonstrated in the case of the French Wars of Religion, there were often numerous small states and territories that sometimes rivaled larger ones in power, and even nobles that were part of a given kingdom had the right to raise and maintain their own armies outside of the direct control of the monarch.

That changed starting in the early seventeenth century, primarily in France. What emerged was a stronger, centralized form of monarchy in which the monarch held much more power than even the most powerful nobleman. Royal bureaucracies were strengthened, often at the expense of the decision-making power and influence of the nobility, as non-noble officials were appointed to positions of real power in the government. Armies grew and, with them, the taxation to support them became both greater in sheer volume and more efficient in its collection techniques. In short, more real power and money flowed to the central government of the monarch than ever before, something that underwrote the expansion of military and colonial power in the same period, as well as a dazzling cultural show of that power exemplified by the French “sun king,” Louis XIV.

Terms for Identification

The exemplary case of absolutist government coming to fruition was that of France in the seventeenth century. The transformation of the French state from a conventional Renaissance-era monarchy to an absolute monarchy began under the reign of Louis XIII, the son of Henry IV (the victor of the French Wars of Religion). Louis XIII came to the throne as an eight-year-old when his father was assassinated in 1610. Following conventional practice when a king was too young to rule, his mother Marie de Medici held power as regent, one who rules in the name of the king, enlisting the help of a brilliant French cardinal, Armand de Richelieu. While Marie de Medici eventually stepped down as regent, Richelieu joined the king as his chief minister in 1628 and continued to play the key role in shaping the French state.

Cardinal Richelieu, in many ways the architect of absolute monarchy in France.

Richelieu deserves a great deal of the credit for laying the foundation for absolutism in France. He suppressed various revolts against royal power that were led by nobles, and he created a system of royal officials called Intendants, royal governors who were men who were usually not themselves noble but were instead drawn from the mercantile classes. They collected royal taxes and supervised administration and military recruitment in the regions to which they were assigned; they did not have to answer to local lords.

Richelieu’s major focus was improving tax collection. To do so, he abolished three out of six regional assemblies that, traditionally, had the right to approve changes in taxation. He made himself superintendent of commerce and navigation, recognizing the growing importance of commerce in providing royal revenue. He managed to increase the revenue from the taille, the direct tax on land, almost threefold during his tenure (r. 1628 – 1642). That said, while he did curtail the power of the elite nobles, most of those who bore the brunt of his improved techniques of taxation were the peasants; Richelieu compared the peasants to mules, noting that they were only useful for working.

Richelieu was also a cardinal: one of the highest-ranking “princes of the church,” officially beholden only to the pope. His real focus, however, was the French crown. It was said that he “worshiped the state” much more than he appeared to concern himself with his duties as a cardinal. He even oversaw French support of the Protestant forces in the Thirty Years’ War as a check against the power of the Habsburgs, and also supported the Ottoman Turks against the Habsburgs for the same reason. Just to underline this point: a Catholic cardinal, Richelieu, supported Protestants and Muslims against a Catholic monarchy in the name of French power.

Louis XIII died in 1643, and his son became king Louis XIV. The latter was still too young to take the throne, so his mother became regent, ruling along Richelieu’s protégé, Jules Mazarin, who continued Richelieu’s policies and focus on taxation and royal centralization. Almost immediately, however, simmering resentment against the growing power of the king exploded in a series of uprisings against the crown known as The Fronde, essentially a noble-led civil war against the monarchy (the rebels even formed a formal alliance with Spain). They were defeated by loyal forces in 1653, but the uprisings made a profound impression on the young king, who vowed to bring the nobles into line.

When Mazarin died in 1661, Louis ascended to full power (he was 23). Louis went on to a long and dazzling rule, achieving the height of royal power and prestige not just in France, but in all of Europe. He ruled from 1643 – 1715 (including the years in which he ruled under the guidance of a regent) meaning he was king for an astonishing 54 years; consider the fact that the average life expectancy for those surviving infancy was only about 40 years at the time(!). Louis was called the Sun King, a term and an image he actively cultivated, declaring himself “without equal,” and being depicted as the sun god Apollo (he once performed as Apollo in a ballet before his nobles, to rapturous applause – he was an excellent dancer). He was, among other things, a master marketer and propagandist of himself and his own authority. He had teams of artists, playwrights, and architects build statues, paint pictures, write plays and stories, and build buildings all glorifying his image.

Famously, Louis developed what had begun as a hunting lodge (first built by his father) in the village of Versailles, about 15 miles southeast of Paris, into the most glorious palace in Europe, built in the baroque style and lavishly decorated with ostentatious finery. Over the decades of his long rule, the palace and grounds of the Palace of Versailles grew into the largest and most spectacular seat of royal power in Europe, on par with any palace in the world at the time. There were 1,400 fountains in the gardens, 1,200 orange trees, and an ongoing series of operas, plays, balls, and parties. 10,000 people could live in the palace, counting its additional buildings, since Louis ultimately had 2,000 rooms built both in the palace and in apartments in the village, all furnished at the state’s expense. The grounds cover about 2,000 acres, or just over 3 square miles (by comparison, Central Park in New York City is a mere 843 acres in size).

A contemporary photograph of the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles, a spectacular example of baroque architecture and interior design.

Louis expected high-ranking nobles to spend part of the year at Versailles, where they were lodged in apartments and spent their days bickering, gossiping, gambling, and taking part in elaborate rituals surrounding the person of the king. Each morning, high-ranking nobles greeted the king as he awoke (the “rising” of the king, in parallel to the rising of the sun), hand-picked favorites carried out such tasks as tying the ribbons on his shoes, and then the procession accompanied him to breakfast. Comparable rituals continued throughout the day, ensuring that only those nobles in the king’s favor ever had the opportunity to speak to him directly. The rituals were carefully staged not only to represent deference to Louis, but to emphasize the hierarchy of ranks among the nobles themselves, undermining their unity and forcing them to squabble over his favor. One of the simplest ways in which Versailles undermined their power was that it cost so much to maintain oneself there – about 50% of the revenue of all but the very richest nobles present in the town or the château was spent on lodging, clothes, gifts, and servants.

Around the king’s person, courtiers had to be very careful to wear the right clothes, make the right gestures, use the correct phrases, and even display the correct facial expressions. Deviation could, and generally did, lead to humiliation and a sometimes permanent loss of the king’s favor, to the delighted mockery of the other nobles. This was not just an elaborate game: anyone wishing to “get” anything from the royal government (e.g. having a son appointed as an officer in the army, joining an elite royal academy of scholars, securing a lucrative royal pension, serving as a diplomat abroad, etc.) had to convince the king and his officials that he was witty, poised, fashionable, and respected within the court. One false move and a career could be ruined. At the same time, the rituals surrounding the king were not invented to humiliate and impoverish his nobles per se; instead, they celebrated each noble’s power in terms of his or her proximity to the king. Nobles at Versailles were reminded of two things at once: their dependence and deference to the king, but also their own dignity and power as those who had the right to be near the king.

Not just nobles participated in the dizzying web of favor-trading, gossip, and bribery at Versailles, however. Perhaps surprisingly, any well-dressed person was welcome to walk through the palace and the grounds and confer with those present (Louis XIV prided himself on the “openness” of his court, contrasting it with the closed-off court of a tyrant). Both men and women from very humble origins sometimes rose to prominence, and made a healthy living, at Versailles by serving as go-betweens for elites seeking royal positions in the bureaucracy. Others took advantage of the state’s desperate need for revenue by proposing new tax schemes; those that were accepted usually came with a payment for the person who submitted the scheme, so it was possible to make a living by “brainstorming” for tax revenue on behalf of the monarchy. Despite the vast social gap between the nobility and commoners, many nobles were perfectly happy to form working relationships with useful social inferiors, and in some cases real friendships emerged in the process.